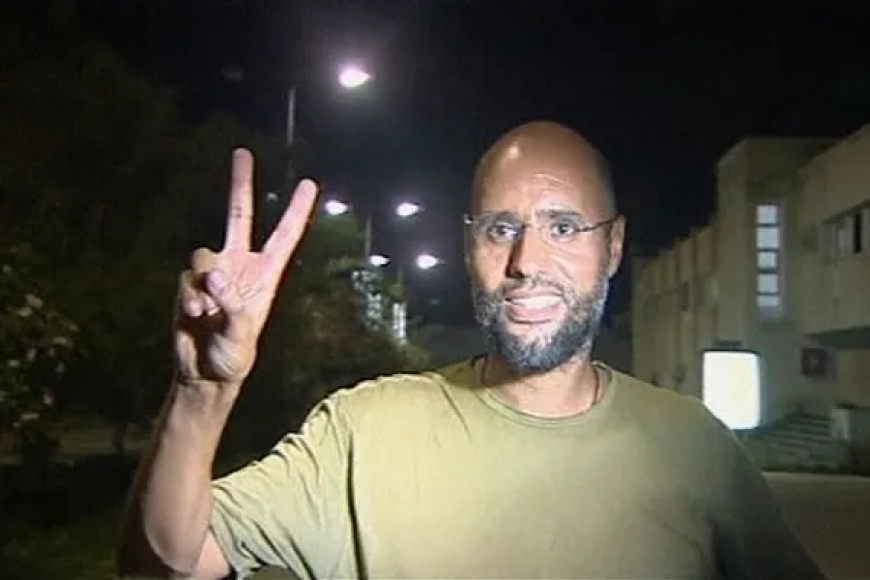

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, son of former leader, killed in Libya

Gaddafi’s political team says masked men killed him at his home in Zintan in a ‘cowardly and treacherous assassination’.

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the most prominent son of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, has been killed in Libya, according to officials and local media.

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi’s lawyer, Khaled al-Zaidi, and his political adviser, Abdulla Othman, announced the 53-year-old’s death in separate posts on Facebook on Tuesday, without providing details.

Libyan news outlet Fawasel Media cited Othman as saying that armed men killed Gaddafi in his home in the town of Zintan, some 136km (85 miles) southwest of the Libyan capital, Tripoli.

Gaddafi’s political team later released a statement, saying that “four masked men” stormed his house and killed him in a “cowardly and treacherous assassination”.

The statement said that he clashed with the assailants, who closed the security cameras at the house “in a desperate attempt to conceal traces of their heinous crimes”.

Khaled al-Mishri, the former head of the Tripoli-based High State Council, an internationally recognised government body, called for an “urgent and transparent investigation” into the killing in a social media post.

Gaddafi never had an official position in Libya, but was considered to be his father’s number two from 2000 until 2011, when Muammar Gaddafi was killed by Libyan opposition forces, ending his decades-long rule.

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was captured and imprisoned in Zintan in 2011 after attempting to flee the North African country following the opposition’s takeover of Tripoli.

He was released in 2017 as part of a general pardon and had lived in Zintan since.

Heir apparent

Born in June 1972 in Tripoli, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was the second-born son of Libya’s longtime ruler.

A Western-educated and well-spoken man, Gaddafi presented a progressive face to the oppressive government run by his father, and he played a leading role in a drive to repair Libya’s relations with the West, beginning in the early 2000s.

He led talks on Libya abandoning its weapons of mass destruction and negotiated compensation for the families of those killed in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988.

Educated at the London School of Economics and a fluent English speaker, he also championed himself as a reformer, calling for a constitution and respect for human rights. His dissertation dealt with the role of civil society in reforming global governance.

But when the rebellion broke out against the elder Gaddafi’s long rule in 2011, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi immediately chose family and clan loyalties, becoming an architect of the brutal crackdown on dissidents, whom he called rats.

Speaking to the Reuters news agency at the time of the popular uprising in Libya in 2011, he said: “We fight here in Libya, we die here in Libya.”

He warned that rivers of blood would flow and that the government would fight to the last man, woman and bullet.

“All of Libya will be destroyed. We will need 40 years to reach an agreement on how to run the country, because today, everyone will want to be president, or emir, and everybody will want to run the country,” he said.

Gaddafi was accused of torture and extreme violence against opponents of his father’s rule, and by February 2011, he was on a United Nations sanctions list and banned from travelling. He was also wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged crimes against humanity committed in 2011.

After the rebels took over the capital, Tripoli, he tried to flee to neighbouring Niger dressed as a Bedouin tribesman. But he was captured by the Abu Bakr Sadik Brigade militia on a desert road and flown to Zintan.

Following long negotiations with the ICC, Libyan officials were granted authority to try Gaddafi for alleged war crimes. In 2015, a Tripoli court sentenced him to death in absentia.

After his release from detention in 2017, he spent years underground in Zintan to avoid assassination.

In November 2021, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi announced his candidacy in the country’s presidential election in a controversial move that was met with outcry from anti-Gaddafi political forces in western and eastern Libya.

As the election process ground on that year with no real agreement on the rules, Gaddafi’s candidacy became one of the main points of contention. He was disqualified because of his 2015 conviction, but when he tried to appeal the ruling, fighters blocked off the court.

The ensuing arguments contributed to the collapse of the election process and Libya’s return to political deadlock.