Power privilege and the downfall of a dynasty

For generations, the Murdaugh family dominated their rural swath of South Carolina – then Alex Murdaugh was accused of the brutal murders of his wife and son. What followed was the stunning unravelling of a life of power and privilege, exposing embezzlement, drug abuse and a failed hitman suicide plot.

You may find some language offensive.

In the fifth week of his murder trial, Alex Murdaugh took the stand.

Over nearly 10 hours testifying in his own defence, the crowded courtroom in Walterboro, South Carolina, would see two versions of Mr Murdaugh. One seemed tired, his voice lilting and thin. His clothes hung loose; months in prison had whittled down his formerly heavy frame. He rocked back and forth, shook his head from side to side, and wept.

The other seemed much more like the man that other witnesses had described – savvy and charming, once a formidable player in the state’s clubby legal circuit. This Mr Murdaugh addressed the jury directly, was relaxed and in control.

“What a tangled web we weave,” he told them.

Directly ahead of him, on the rear wall of the courtroom, there was a rectangular-shaped sun stain where a painting used to be – a portrait of his namesake, his great-grandfather Rudolph “Buster” Murdaugh, which had been taken down for the trial.

For nearly a century, the Murdaugh family reigned in this southern corner of South Carolina – a flat expanse of marshlands, palm trees and porch-ringed houses – presiding over the local prosecutor’s office and the private law firm that made them rich.

But since the brutal killings of his wife, Maggie, and son, Paul, in June 2021, a series of bizarre and tragic events helped bring about Mr Murdaugh’s spectacular fall from grace. The 54 year old has denied the murders, which prosecutors allege were a desperate diversion from decades of financial wrongdoing. But on the stand, he admitted to a number of other crimes, including embezzlement, fraud and a faked assassination attempt.

The trial has become one of the most closely-watched in the country. It has exposed what some see as the apparently unchecked power of the Murdaugh family in their small community, and brought about the undoing of a local dynasty.

“This is what happens when average people have no checks and balances,” said Bill Nettles, former US attorney for South Carolina.

“And there were no checks and balances on him.”

To know South Carolina’s Lowcountry is to know the Murdaugh family name. Between 1920 and 2006, three generations of Murdaugh men presided as the chief prosecutor for the state’s Fourteenth Judicial Circuit, the longest such stretch of family control in United States history.

“They were the law,” Mr Nettles said.

For even longer, the Murdaughs worked at the family-founded litigation firm – Peters, Murdaugh, Parker, Eltzroth & Detrick (PMPED) – amassing a small fortune and building out their dominance in all corners of the Lowcountry. By all accounts, in a region where personal injury firms thrived, theirs was the best.

“They could get a verdict that would exceed the norm dramatically,” said South Carolina lawyer Joe McCulloch.

“And when I say exceed the norm – they could turn a $100,000 case into a million dollar settlement.”

Their judicial circuit became known as a mecca for plaintiffs. Corporations who could avoid it reportedly skipped the area entirely.To juries, locals said, the Murdaughs were familiar faces – a reliable advantage at trial.

“When people graduated high school, they would send gifts; they paid for funerals, sent flowers to people who were in the hospital,” said Eric Bland, a malpractice attorney based in South Carolina. “They salted the town with goodwill.”

From their two offices in Hampton, the Murdaughs established themselves as a de facto authority of the Lowcountry. Their influence was not wide – it did not even span the width of the state – but it was deep. In the small, insular community where they lived, residents said, the Murdaugh family ruled.

“We all knew them,” said one waitress in town, who also didn’t want to give her name, saying she didn’t want to “get in trouble” for speaking out of turn. She also didn’t want to be recorded. “You’re just going to have to remember this,” she said. “They had power. And they took it too far.”

In the third week of the trial, the former chief financial officer of PMPED Jeanne Seckinger described Alex Murdaugh’s approach as a lawyer. “The art of bullshit, basically,” she said.

Mr Murdaugh’s success was due “not from his work ethic”, Ms Seckinger said, “but his ability to establish relationships and manipulate people into settlements and clients into liking him.”

That work made him rich, millions of dollars that fed his family’s wealthy lifestyle – a speedboat, a beach house, their sprawling 1,700 acre hunting property called Moselle, and a staff to assist. But the success, seemingly a Murdaugh birthright, belied his secret: a raging addiction to painkillers and years of theft, fraud and embezzlement.

On the stand in Walterboro, Mr Murdaugh tearfully admitted to taking millions from settlements meant for his clients, stealing $3.7m (£3m) in 2019 alone. It was wrong, he said, but he was desperate: his addiction had drained his bank accounts.

State prosecutors painted a picture of fraud and theft at an almost implausible scale, and of a perpetrator convinced of his impunity. Mr Murdaugh, they allege, stole indiscriminately from colleagues and clients, the young and old, the disabled and sick. He faces nearly 100 separate financial charges.

For years, Ms Seckinger testified, she had noticed yellow flags, small irregularities in Mr Murdaugh’s files. But the firm was a “brotherhood”, she said. “They trusted him.”

Tony Satterfield was another person who trusted Mr Murdaugh. When Mr Satterfield’s mother, Gloria – the Murdaugh’s housekeeper for 20 years – died after a fall at work, Mr Murdaugh told Tony and his brother they should file a wrongful death suit against him, and that his home insurance would pay compensation. He even suggested a lawyer who could help sue him.

Two of Mr Murdaugh’s insurance policies paid out a total of $4.3m, but the Satterfields did not receive a dime. They did not even know the case had been settled. Alex Murdaugh, as he himself admitted in court, had stolen it.

“I feel like if someone had paid closer attention, they would have figured this out,” said Eric Bland, the malpractice lawyer who represented the Satterfields against Mr Murdaugh. “But those kids revered the Murdaughs, they trusted him.”

One year after Gloria Satterfield died, there was another fatal accident in the Murdaugh family orbit. But this time, prosecutors allege, the tragedy would present a problem that Alex Murdaugh could not contain.

Late in the evening of 24 February 2019, Paul Murdaugh was aboard the family boat when it rammed headlong into a bridge, throwing three of the six passengers – all young adults – into the cold water below. One of them, 19-year-old Mallory Beach, was killed, her body recovered days later in a marsh several miles away.

At the time of impact, according to all of the other passengers, Paul had been driving. A blood test would find the 19-year-old Murdaugh’s blood alcohol level was three times the legal limit.

Taken together, witness testimony from the night renders an image of Mr Murdaugh hellbent on insulating his son. He roamed from room to room, they said, trying to speak to the teenagers. A nurse said he looked like he was trying to “orchestrate something”. One passenger, Connor Cook, said in a deposition he was told by Mr Murdaugh “to keep my mouth shut”. He was scared, he said, “them being who they are”.

On the stand last week, Mr Murdaugh called any claims that he had “fixed witnesses” or influenced any part of the boat wreck investigation “totally false”.

Still, to those in the Lowcountry, the boat crash was seen “as a test of the system”, said Mandy Mattney, a reporter based in South Carolina who has led coverage of the Murdaughs since 2019. “Everyone in Hampton really believed that Paul wouldn’t be charged.”

Months later, however, Paul was charged with three crimes, including boating under the influence resulting in death. He pleaded not guilty to the charges but died before he faced trial.

Looking back now, it may have been the moment Alex Murdaugh’s life began to unravel.

The family of Mallory Beach hired a lawyer named Mark Tinsley to represent them in a wrongful death suit against Mr Murdaugh that could have resulted in millions in damages.

Mr Murdaugh claimed he was broke. “I didn’t believe it,” Mr Tinsley said during the trial this month.

So Mr Tinsley filed a motion to compel Mr Murdaugh to disclose his finances. A hearing on the matter was scheduled for 10 June, 2021. The disclosure would reveal his years of corporate fraud.

“The fuse was lit,” Mr Tinsley said.

On 7 June 2021, three days before the hearing on his finances was scheduled, Alex Murdaugh called 911. His wife Maggie and son Paul had been shot, he said.

By the time the first sheriff’s deputy arrived at Moselle, Mr Murdaugh told him his theory: Paul and Maggie had been killed in retaliation for the boat accident.

“He’s getting threats,” Mr Murdaugh said of his son. “I know that’s what it is.”Many in the Lowcountry believed him, and with Paul dead, the wrongful death lawsuit stalled.

But three months later, Mr Murdaugh called 911 again, this time to report that he had been shot in the head on the side of a rural road. He later admitted to arranging a hit on himself so that his surviving son, Buster, could collect on his life insurance. As the ploy fell apart, his firm disclosed they had pushed him out just the day before the incident over alleged embezzlement.

For months, the mystery of Maggie and Paul’s murders deepened as authorities said little about the case, offering no clues about suspects or motive. Then, in July 2022, Mr Murdaugh was arrested in connection with the killings.

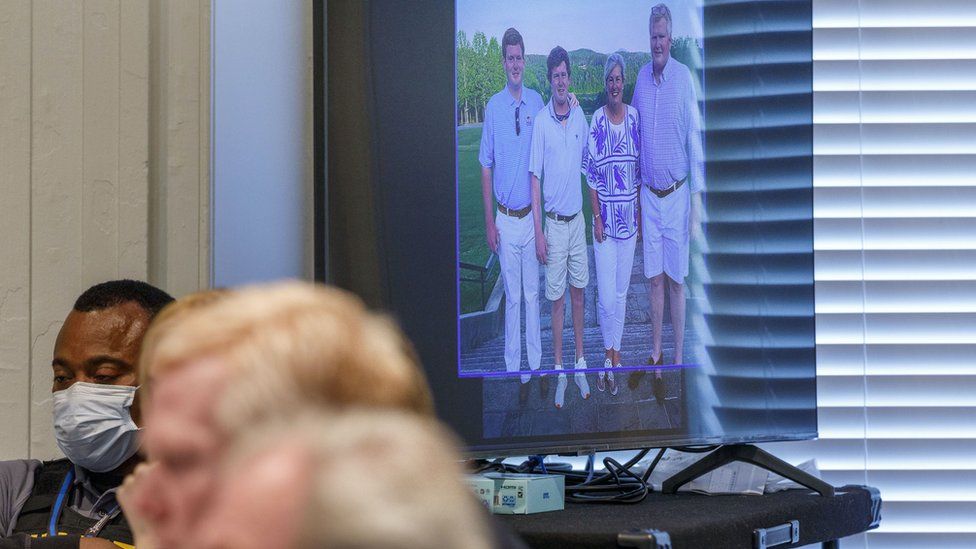

Image source, Grace Beahm Alford/The Post and Courier/Poo

For more than a month now, Alex Murdaugh’s downfall has drawn early morning crowds to the Walterboro courthouse, a line too long to fit inside. Upstairs, in the courtroom’s cool air, spectators in suits and sundresses have filled row after row of the dark wooden pews that line the room. At times, the mood has felt strangely like a church reception, Mr Murdaugh’s brother and son milling around, offering handshakes and tepid smiles.

The prosecution and defence will present closing arguments in the coming days before the jury retires to consider its verdict.

Here in the Lowcountry, many said they believed Alex Murdaugh was at the end of the line.

But for decades, the Murdaugh family has made an ally out of juries, walking out of courtrooms with the judgments that built their fortunes and cemented their influence.

Alex Murdaugh’s fate will be decided the same way, perhaps a final test of his influence in a case where all the evidence is circumstantial – there was no murder weapon found, no blood on Mr Murdaugh’s t-shirt that night, no eyewitnesses to the killings.

And his decision to testify – both an unusual move and a legal risk – was perhaps a testament to an enduring self-belief, a confidence in his ability to sway people, like he has done for years.

“I can promise you I would hurt myself before I would hurt one of them,” he said last week. “Without a doubt.“